|

Secure Site

Secure Site

|

|

Archive for the 'Dreams' Category

What Do Dreams Mean...Kasamori Osen Ippitsusai Buncho Recent developments in dream research won’t make sense without first touching on the academic thunderbolt of 1977, when a paper by two Harvard neurophysiologists, Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley, ran in the American Journal of Psychiatry. At the time, Sigmund Freud’s theory of dreams (which holds, in part, that dreams preserve sleep by distracting the brain with reflections of the unconscious) was a pillar of psychiatry. In The Brain as a Dream State Generator: An Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis of the Dream Process, the Harvard pair challenged Freudian theory on virtually every point. They argued that dreams are nonsense created when the forebrain makes “the best of a bad job in producing even partially coherent dream imagery from the relatively noisy signals” sent up to it from the brain stem at the onset of REM. Their paper served to yank dreaming from the realms of the psychological and plonk it in a dreary, physiological bucket.

Later, the English molecular biologist Francis Crick, a co-discoverer in the 1950s of the structure of the DNA molecule, drained a little more romance from dreaming. His and theoretical biologist Graeme Mitchison’s “reverse learning” theory held that dreams rid the brain of superfluous notions, and that without this regular flushing brain overload would manifest as hallucinations and obsessions. There are echoes of this idea in the perspective of Drew Dawson, director of the University of South Australia’s Centre for Sleep Research: “I tend to think of dreaming as a bit like backwashing the swimming pool filter.”

While hugely influential, Hobson and McCarley’s Activation-Synthesis model attracted hordes of critics, who protested that many dreams aren’t merely cognitive fragments nor a succession of chaotic images, but so story-like, sequential and dramatic that the thinking brain must surely have played a more substantial role in their production than the last-minute editing of a pile of neural bloopers. And there’s the matter of lucid dreaming, in which people become aware in the course of a dream that they are, in fact, dreaming, and are able to control the course of events—a phenomenon that strengthens the case for higher-brain involvement in dream construction. The lucid dreamer can apparently apply certain techniques to prolong the dream and take it in delightful directions. “The experiences are so convincing,” says Victoria University’s Bruck, “it seems as if another level of reality exists.”

Dreams Serve to Process Memories But the wrecking job on the notion that dreams are a random by-product of REM sleep was carried out by the South African neuroscientist and psychoanalyst Solms, who was working at the Royal London Hospital in the 1990s when he made his career-defining discoveries. Solms wasn’t alone at the time in realizing that dreaming occurred outside periods of REM, that it was also common at sleep onset and shortly before waking in the morning. But he found an even weaker spot in the Hobson-McCarley hypothesis. If their theory was right, then people with damage to a part of the brain stem called the pons—the on-off switch for REM sleep—shouldn’t be having dreams. Solms, however, had five patients with lesions in precisely that region, and while they weren’t having REM, they were nonetheless reporting dreams.

Even more interesting to Solms were 53 Royal London Hospital patients with healthy brain stems who said they’d stopped dreaming. Most of them had damage to the part of the brain that generates spatial imagery. That made sense: if you can’t create pictures in your mind, how are you going to dream? It was the circumstances of the remaining nine patients that fascinated Solms. They had damage to the white matter of the ventromesial quadrant of the frontal lobes, an area linked to the transmission of the chemical dopamine and crucially involved in motivation, urges and cravings. These patients still experienced REM sleep but reported having lost both the capacity to dream and all sense of spontaneity, drive and love of life. They did what they were told and that was about it.

It seemed to Solms that dreams must themselves be associated with driving urges—a very Freudian take—but he needed more evidence in the form of more people with lesions in this particular spot. Nowadays, damage to that part of the brain is rare, normally a result of strokes or tumors. But it was a lot more common in the ’50s and ’60s when some mental illnesses were treated by removing it in an operation called a prefrontal leukotomy. Solms waded through the literature and found hundreds of case studies in which the effects of this procedure were described. To his amazement, reported loss of dreaming was one of them. “So I thought I’d discovered something new,” says Solms, “but it turned out to be something we’d documented long ago but had forgotten.” In the field of dreams, however, his findings were no less significant for that: Solms had shown REM and dreaming to be dissociable states and produced a compelling case that the higher brain has the central role in dream creation.

Solms, who believes science is getting closer to answering the key questions about dreaming, is leading two studies at the University of Cape Town with that goal in mind. One involves using functional magnetic resonance imaging to try to disentangle the REM brain from the dreaming brain. He wants to obtain images of the dreaming/non-dreaming brain at sleep onset and note the differences between the two. “If we can image what’s going on at that point, then we’ll get a clear handle on what mechanisms are important for dreaming as opposed to REM sleep,” says Solms, who predicts a key role for the motivational part of the brain.

His other study involves comparing the sleeping ability of subjects who dream with that of subjects who can’t because of brain lesions. Solms argues that because our motivational drive is fully active while we’re asleep, our brain’s way of keeping us asleep and undertaking the necessary repairs is by tricking us, through dreams, into thinking we’re up and about and pursuing our desires. It’s the neurological equivalent of putting on a DVD for the kids so the main players in the house can get some shut-eye. “Dreams replace the real actions that are instigated by our motivational impulses while we’re awake,” Solms says. His hunch is that the non-dreamers in his study will wake up more often during the night than the dreamers, especially during REM sleep: “The dream,” he says, “is what keeps you asleep.”

Others approach dreams from a different angle. An argument that resonates with many is that whatever the explanation for dreaming, humans must do it for the same reason that all mammals have done it for more than 100 million years; any theory must make as much sense when applied to a rabbit as to a person. In the same Darwinian vein, sleeping and dreaming must serve important functions because they’re vulnerable states and natural selection would have eliminated them if they didn’t provide compensating benefits. In the ancestral environment, human life was short and perilous; ever-lurking predators threatened survival and reproductive success. The biological function of dreaming, argues Antti Revonsuo, professor of psychology at the University of Turku, Finland, is to simulate threatening events so to prepare the dreamer for recognizing and avoiding danger.

Why do We Dream? The threat-simulation theory, first presented in 2000, “is built on the actual empirical evidence we have concerning the content of dreams,” Revonsuo says. “It’s surprising how many theories of dreaming there are that are not based on any systematic review of the evidence.” He cites studies showing that, typically, dreams are too seldom sweet, and that negative feelings, dangerous scenarios and aggression are over-represented. Based on ongoing work with PhD student Katja Valli, Revonsuo estimates that the average “non-traumatized” young adult has, conservatively, 300 threat-simulation dreams a year. In the dreams of both men and women, male strangers and wild animals are most often the enemy, and the dreamer’s typical responses are running and hiding, often in a state of terror.

If dreams are biased toward simulating ancestral threats, the traces of these biases would be strongest early in life, before the brain has adjusted to the realities of the contemporary environment. Sure enough, Revonsuo says, research shows that animals make up about 30% of all characters in the dreams of children aged 2-6 compared to 5% of adults’. True, the animals of children’s dreams are often fluffy and harmless, but almost half the time they’re frightening creatures—snakes, bears, lions, gorillas—that children would seldom, if ever, have encountered in waking life.

The reason we don’t dream about reading and writing, Revonsuo speculates in his original paper, is not because these activities don’t engage our emotions but because they’re “cultural latecomers that have [yet] to be effortlessly hammered into our evolved cognitive architecture.” Revonsuo knows that his theory pleases neither Freudians nor neuroscientists. “If, for the supporters of the psychological theories, it grants too little meaning to dreams,” he says, “for the supporters of neurophysiological random-noise theories, it grants dreaming far too much.”

Harvard’s Stickgold believes dreams have a different function entirely. “I think it’s pretty clear now that sleep and dreaming serve to process memories from the last day and all the way back,” he says. “Sleep can strengthen memories… and help extract the meaning of events by building associative networks with other memories. Dreaming is probably a high-level version of this processing.” Clearly, he adds, you don’t have to remember your dreams for these processes to work. “The brain is tuning your memory circuits as you sleep, and remembering the imagery created during this process may be fun, may be instructive, but is almost undoubtedly a freebie.”

Stickgold’s evidence includes an experiment he led in 2000 when Harvard researchers were able to elicit the same dream in a bunch of people as they drifted off to sleep. They did this by exposing 27 subjects to an intensive three-day course in the computer game Tetris, which involves assembling geometric shapes. By the second night of training, 17 subjects had reported having the same dream image—falling Tetris pieces—indicating to Stickgold that the need to learn prods the brain to dream. More of these kinds of studies are needed, he says, “because as we learn to manipulate dream content, we can start to figure out what the rules are that the brain uses in selecting material for our dreams.” Though not sold on the memory-consolidation theory, the Dream & Nightmare Laboratory’s Nielsen sees merit in it. Of course, if dreaming does embed memories it’s doing it in ways we don’t understand, he says. “Perhaps memory needs to be sliced and diced and then reassembled in odd ways in order for consolidation to be maximized.”

Psychotherapists tend to regard a lot of the research into dreaming as missing the point. Scientists, they say, can theorize all they like about dreaming’s function and physiological underpinnings, but why dreams matter is their effect on the dreamer. The man contemplating an extramarital affair dreams of the dire consequences of having one. He awakens to feel not only exquisite relief that he was dreaming but determined to walk the line. If, as Solms believes, dreams spring from the motivational part of our brain at a time when other parts that inhibit us are off-line, “it follows that there’s value in interpreting dreams,” he says. They provide a “privileged, unfiltered access” to what’s on a person’s mind. Mark Blagrove, a lecturer in psychology at the University of Wales, where he runs a sleep laboratory, thinks it’s possible the search for a biological function of dreaming could be futile. “It could just be,” he says, “that our elaborate dreams are a side effect of the fact that we have a highly evolved imagination.”

All the competing theories on why we dream may be wrong. One or more of them could be right. “I have no doubt that dreams can be enjoyable, informative, even revelatory to the dreamer,” says Harvard’s Stickgold. “But dream analysis is a more tricky question. The more dogmatic and doctrinaire the beliefs of the analyst, the less useful and potentially more destructive the analysis process becomes.” People should understand, he adds, that dreams aren’t constructed with the goal of delivering a message; they don’t have an inherent meaning. “But when you look at your dreams after you wake up… you can often feel the associative networks that were activated during dream construction, and trace them back a ways, and maybe discover a new way of looking at events in your life, of looking at yourself, at others, or at the world at large.” Maybe that’s worth a third of our lives asleep, perchance dreaming.

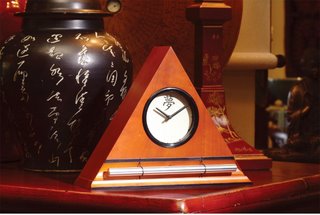

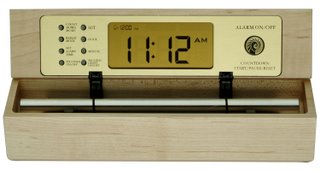

Boulder, Colorado—an innovative company has taken one of life’s most unpleasant experiences (being startled awake by your alarm clock early Monday morning), and transformed it into something to actually look forward to. “The Zen Alarm Clock,” uses soothing acoustic chimes that awaken users gently and gradually, making waking up a real pleasure. Rather than an artificial recorded sound played through a speaker, the Zen Clock features an alloy chime bar similar to a wind chime.

When the clock’s alarm is triggered, its chime produces a long-resonating, beautiful acoustic tone reminiscent of a temple gong. Then, as the ring tone gradually fades away, the clock remains silent until it automatically strikes again three minutes later. The frequency of the chime strikes gradually increase over ten-minutes, eventually striking every five seconds, so they are guaranteed to wake up even the heaviest sleeper. This gentle, ten-minute “progressive awakening” leaves users feeling less groggy, and even helps with dream recall.

adapted form Time.com, by Daniel Williams

Gentle Chime Alarm Clock for a Progressive Awakening Now & Zen – The Zen Alarm Clock Store

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

Posted in Bamboo Chime Clocks, Chime Alarm Clocks, Dreams, sleep, Sleep Habits

The Dream-Health Connection Physicians in early Egypt and ancient Greece encouraged people to recall their dreams when seeking medical advice. Mexican and Native American shamans have long considered dream interpretation important for both healing and spiritual awareness. Tibetan medicine views dream work as a path to self-discovery, an awareness that can help create an inner balance — and inner balance contributes to good health.

The Dream-Health Connection

Indeed, the study of dreams in relation to health is gaining acceptance in the scientific community. One study reveals that the role of REM sleep and noting dream variables may be significant in helping patients gain quicker remission from marital separation-related depression (Psychiatry Research, 1998, vol. 80). Other research finds that dream content reflects waking life stressors in people with insomnia. Several studies tracked cancer patients’ dream series and reported that their dreams may have pointed to early cues for the presence of the disease process.

Katherine O’Connell, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist, dream analyst and founder of the Dream Institute in Santa Cruz, Calif., says that “listening to dreams can save your life.” She notes that dreams not only reveal symbols for health issues that need to be resolved, but they often reveal the herbal remedy for the problem — a method of medical dream work that dates back to ancient Egypt and Greece. For example, O’Connell finds that her clients often dream of flowers or herbs that are traditionally used to treat the ailments their physicians diagnose.

In her dream-work journey, O’Connell has studied dream medicine with Tibetan lamas and researched 3,500-year-old Egyptian homeopathic remedies used for dream recall. Through the process, she has also collected more than 5,000 dreams — her own and those of clients — for analysis.

O’Connell believes that viewing your dreams as a series is the best way to understand the complete picture of your physical and psychological health. She suggests writing your dreams down, then reviewing common threads that run through them. “I see dream work as a good mystery story with many chapters,” she says. “With each chapter, we gain more clues along the way.”

Cultivating Dream Awareness

To access the clues in your dreams, start with your knowledge of yourself. While dream symbol books can serve as loose guides, dream interpretation is really an individual matter. For example, the color green may represent money to your spouse but symbolize healing energy to you. Likewise, a spider can be your personal symbol of creativity whereas it may signal a venomous threat to someone else; similar dream images often have different interpretations for different people. So it’s important to tap into your own associations, feelings and intuition about your dream symbols. “We have such innate wisdom. We must remember to trust ourselves,” O’Connell says.

Want to be more in touch with your dreams? ASD offers the following tips:

- Remind yourself to remember your dreams before you fall asleep.

- Keep a pad of paper and pen or tape recorder by your bedside. As you awaken to your chiming Zen Alarm Clock , try to move as little as possible and try not to think right away about your upcoming day. Instead, immediately write down your dreams and dream images, as they can fade quickly if not recorded.

- Influence your dreams by giving yourself pre-sleep suggestions. Before going to bed, write down your agenda. Or say aloud what you want to know to strengthen the conscious-subconscious dream connection.

- Forgo taking alcohol or stimulants such as coffee or caffeinated tea before bed, as these substances interfere with REM sleep. Also, try taking a warm bath with a few drops of chamomile or cedar essential oil (first diluted in a carrier oil such as almond or walnut), or try practicing a few minutes of meditation to clear your mind for restful sleep and clearer dreams. Dreams not only have the potential to enhance your health but, as Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz says, “Dreams show us how to find meaning in our lives, how to fulfill our own destiny and how to realize the greater potential of life within us.”

Sweet dreams.

adapted from Delicious Living, October 2000 by Deborahann Smith

Zen Alarm Clocks with a progressive chime that doesn't interrupt your dreams Now & Zen – The Zen Alarm Clock Shop

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

Posted in Dreams, Japanese Inspired Zen Clocks, Natural Awakening, sleep, Sleep Habits, Zen Alarm Clock

The Zen Alarm Clock transforms mornings, awakening you gradually with a series of gentle acoustic chimes Once you use a Zen Clock nothing else will do Deep sleep can provide much needed rest after a difficult day, but a new study suggests it can also help decrease the emotional intensity of painful experiences.

Researchers at the University of California at Berkeley found that the more time spent in REM sleep, or the dream phase of sleep, may diminish the activity of stress-related chemicals in the brain.

“The dream stage of sleep, based on its unique neurochemical composition, provides us with a form of overnight therapy, a soothing balm that removes the sharp edges from the prior day’s emotional experiences,” said Matthew Walker, a co-author of the study and an associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at UC Berkeley in a statement.

Their findings, the authors said, could help explain why people who have with post-traumatic disorder experience recurring nightmares. One of the hallmarks of the disorder is less time spent in REM sleep. As a result, the researchers believe they don’t experience the same emotional blunting brought on by adequate REM sleep. REM sleep normally makes up about 20 percent of normal sleep hours.

In the study, 35 healthy adults were split into two groups. Each group looked at 150 emotional images two different times, 12 hours apart, and an MRI measured brain activity.

Half of the participants stayed awake between each viewing, and the other half got a full night’s in between each viewing.

Those who slept had a less emotional reaction the second time they looked at the images, and the MRI showed less activity in the amygdala, the emotion-processing part of the brain.

Tests that measure brain activity while the participants slept indicated decreased activity of stress-related chemicals, which had a calming effect.

Wake up with gradual, beautiful acoustic chimes. The Zen Alarm Clock transforms your mornings and gets you started right, with a progressive awakening “We know that during REM sleep there is a sharp decrease in levels of norepinephrine, a brain chemical associated with stress,” Walker said. “By reprocessing previous emotional experiences in this neuro-chemically safe environment of low norepinephrine during REM sleep, we wake up the next day, and those experiences have been softened in their emotional strength. We feel better about them, we feel we can cope.”

Boulder, Colorado—an innovative company has taken one of life’s most unpleasant experiences (being startled awake by your alarm clock early Monday morning), and transformed it into something to actually look forward to. “The Zen Alarm Clock,” uses soothing acoustic chimes that awaken users gently and gradually, making waking up a real pleasure.

Rather than an artificial recorded sound played through a speaker, the Zen Clock features an alloy chime bar similar to a wind chime. When the clock’s alarm is triggered, its chime produces a long-resonating, beautiful acoustic tone reminiscent of a temple gong. Then, as the ring tone gradually fades away, the clock remains silent until it automatically strikes again three minutes later. The frequency of the chime strikes gradually increase over ten-minutes, eventually striking every five seconds, so they are guaranteed to wake up even the heaviest sleeper. This gentle, ten-minute “progressive awakening” leaves users feeling less groggy, and even helps with dream recall.

Now & Zen – The Soothing Alarm Clock Store

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

orders@now-zen.com

The Zen Alarm Clock transforms mornings, awakening you gradually with a series of gentle acoustic chimes Once you use a Zen Clock nothing else will do

Posted in Bamboo Chime Clocks, Dreams, sleep, Sleep Habits, wake up alarm clock, Well-being

Wake up with gradual, beautiful acoustic chimes. The Zen Alarm Clock transforms your mornings and gets you started right, with a progressive awakening Dreams are more than just the mini-dramas of your sleeping mind.

Dr. Edward O’Malley, who studies sleep disorders at Norwalk Hospital in Connecticut, says dreaming helps us to process and even memorize information we have encountered throughout the day.

“Even though the situations may be bizarre, there’s a certain logic behind the dream,” he said.

Dreaming also helps to relieve stress and clear the cobwebs from our brains so that we wake up clear and alert.

According to O’Malley, dreams contain a surprising amount of very important content and meaning. He says we should pay close attention.

“While there are general archetype images in dreams like fire and water that mean generic things across the human species, there are very specific cues in your dreams that can give you information that can help you function in the daytime,” he said.

In fact, new research shows dreams help us to solve problems.

“If we have certain conflicts or problems that we may be trying to solve during the daytime,” said Dr. Eric Nofzinger of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, “these problems become reactivated in dreams at nighttime and may get played through.”

Nofzinger’s dream research uses pet scans — an imaging technique — to view the brain’s activity during dream sleep. Remarkably, he has found that the brain’s same emotion centers that are active during the day become active when we dream. Some researchers believe that while we are dreaming, our brains are still working through the emotional conflicts of the day. It is one of the reasons that doctors tell patients to make sure they get enough sleep.

Decoding Dreams

There have been famous examples of people who have dreamed up solutions to problems, said Dr. Deirdre Barrett, a Harvard professor and author of “Trauma and Dreams.”

For example, dreams helped Otto Loewi conceptualize an experiment on a frog heart that later won him the Nobel Prize for medicine and biology. Friedrich August Kekule sorted out the structure of chemistry’s benzene ring in his dreams.

The Zen Alarm Clock's sweet acoustic chimes are truly a gourmet experience “People are going to dream whatever their background and qualifications, and it’s going to be major scientists who have the Nobel Prize-winning dreams,” she said.

She said that there were some steps people could take to focus their dreams in the right direction.

“The best steps are to write the problem down as a brief phrase of a sentence and have a pad and pen by the bed,” she said.

While you are falling asleep, Barrett said, think of the work that you have done so far in solving the problem and form an image to represent it.

“Artists say they like to set up a blank canvas at the other end of the room to suggest I’m looking for an image to paint,” she said.

Barrett suggested telling yourself you want to dream about the image as you are falling asleep.

“The last step, and this is really important, when you first wake up, stay still,” she said. “Don’t jump up and think about something else because recall for dreams is so fragile that you want to recapture it.”

Know What Is Bothering You

Barrett said that people could help determine the outcome of their anxiety dreams by trying to focus on finding a solution to what is troubling them.

“When you’re trying to solve this kind of open-ended problem, you don’t want to script the ending,” she said. “The whole point is to say I want a solution to X but you want to leave it open for your dreaming mind to come through with the solution.”

Boulder, Colorado—an innovative company has taken one of life’s most unpleasant experiences (being startled awake by your alarm clock early Monday morning), and transformed it into something to actually look forward to. “The Zen Alarm Clock,” uses soothing acoustic chimes that awaken users gently and gradually, making waking up a real pleasure.

Rather than an artificial recorded sound played through a speaker, the Zen Clock features an alloy chime bar similar to a wind chime. When the clock’s alarm is triggered, its chime produces a long-resonating, beautiful acoustic tone reminiscent of a temple gong. Then, as the ring tone gradually fades away, the clock remains silent until it automatically strikes again three minutes later. The frequency of the chime strikes gradually increase over ten-minutes, eventually striking every five seconds, so they are guaranteed to wake up even the heaviest sleeper. This gentle, ten-minute “progressive awakening” leaves users feeling less groggy, and even helps with dream recall.

What makes this gentle awakening experience so exquisite is the sound of the natural acoustic chime, which has been tuned to produce the same tones as the tuning forks used by musical therapists. According to the product’s inventor, Steve McIntosh, “once you experience this way of being gradually awakened with beautiful acoustic tones, no other alarm clock will ever do.”

adapted from abcnews.go.com

What makes this gentle awakening experience so exquisite is the sound of the natural acoustic chime

Now & Zen – The Zen Alarm Clock Store

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

orders@now-zen.com

Posted in Bamboo Chime Clocks, Dreams, sleep, Sleep Habits

gentle, chime alarm clocks Fundamentally, dreams — like effective cognitive psychotherapy — “are about abstraction, the ability to pan back, get bigger than, stretch into the remembrance of a larger sense of self,” Naiman says.

And in this hard-charging, info-slurping, sleep-deprived era, in which about 70 million Americans suffer from chronic sleep disorders (and depression is also suspiciously widespread, affecting one in eight women), he and many other sleep experts are more convinced than ever of the link between mental health and a full nightly menu of sleep.

We asked the experts for their best tips to help you get restful sleep — ideally, seven to eight hours of it — that will yield all the dreams you’ve got coming to you.

Drink Moderately, And Mind Your Meds

“A glass of wine with dinner is fine,” Naiman says, but excessive alcohol will cause you to wake up after two or three hours when the sedative effects wear off; this interacts with the first significant REM cycle and disrupts sleep further from there.

Also, many medications — including a number of antidepressants, over-the-counter painkillers, and even, ironically enough, sleeping pills — suppress the hormone melatonin and/or the nutrient choline, both of which mediate REM. It’s always wise, Naiman says, to ask your pharmacist before taking any medicine if it has a REM suppressant and, if it does, whether there’s an alternative.

Utamaro Kitagawa, Bijin Combing Her Hair, 1750-1806 Establish A Presleep Routine

Take a 20-minute soak in a hot bath two hours before bedtime, Cartwright says. The body’s effort to cool itself after the bath mimics the cooling that occurs naturally as our bodies prepare for sleep.

If your logical waking brain is reluctant to let go of the same old anxieties, Cartwright suggests writing down the day’s cares (well before bedtime) in a worry diary, then literally closing the book, telling yourself, I’ve done my worrying for the day.

Create A Restful Environment

Use blackout shades or a sleeping mask to make the room as dark as possible; darkness prompts your brain’s pineal gland to make melatonin. Also, keep your bedroom at a comfortable 60 to 65 degrees; even subtle shifts in body temperature can disrupt sleep cycles.

create a calm environment Put Technology To Work

Relaxation CDs have moved beyond ocean waves; new versions actually have frequencies embedded in the sound tracks to encourage slow-wave sleep. (Check out sound therapist Jeffrey Thompson’s sleep-enhancement collection atneuroacoustic.com.)

Soothe Yourself If You Wake Up

If you have trouble falling back to sleep, Cartwright advises adjusting your strategy depending on the time of night. If you’re waking up after only an hour or so, try some boring mental exercise: See if you can name all 50 states alphabetically, or count backward from 100, inhaling deeply and slowly, then exhaling with each number.

Use a Gentle, Chiming Alarm Clock to wake-up so that you will be calm in the morning.

Woodson Merrell, M.D., chairman of the Department of Integrative Medicine at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City, advises trying to remember the dream you were having when you woke up — even if you can recall only a detail or two — and focusing on it to see if you can drift off again.

If it’s close to your usual wake-up time — say it’s 5 a.m. and you usually wake at 7 — your core body temperature will just be starting to rise to get you active for tomorrow, which may make it hard to go back to sleep, Cartwright says. “The best thing is to take a positive attitude and don’t say to yourself, I’m going to be draggy all day,” she advises. “Instead say, Great, I have two more hours to rest!”

Let Go

“People with insomnia are hyperaroused — pushing, pushing,” Naiman says. “We’re all working so frantically to get a chance to rest. But the paradox is that rest is free.” And, he adds, the great beauty of dreaming — in which “parts of ourselves that recede during waking life” roam freely and creatively — is that “you don’t have to force it to happen. It’s just there for you when you stop.”

Whole Living, November 2010

Text by Louisa Kamps

Now & Zen’s Chime Alarm Clock Store

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

800) 779-6383

choose a chime alarm clock with soothing tones

Posted in Chime Alarm Clocks, Dreams

dreams There’s evidence that creative types may find it easier to dip into the well of their dreams. In one of the largest studies on dream recall and personality traits, conducted at the University of Iowa, subjects who were inclined toward imagination and fantasy in their waking lives were much more likely to remember their dreams and to report dreams with vivid imagery.

The power dreamers also scored higher in terms of “openness,” according to researcher David Watson, who measured their inclination toward novel experiences and different perspectives.

In her book “The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists, and Athletes Use their Dreams for Creative Problem Solving — and How You Can Too,” Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett recounts the stories of notable artists, athletes, and inventors to capture the sly beauty of dream-generated creativity. (My favorite example: In 1844, American inventor Elias Howe, puzzling over how to design sewing machine needles, reportedly woke from a dream in which he was being chased by cannibals carrying spears with holes in their pointed tips. He realized — eureka! — that machine needles would need holes at the front end.)

Barrett has found that 50 percent of people who tell themselves before sleep that they want to dream about a certain dilemma have dreams on their chosen subjects within one week, and that half of them find helpful new information. (The solutions aren’t necessarily as world-shaking as Howe’s. One student struggling to arrange furniture in a cramped apartment woke with a clear diagram of how to fit it all.)

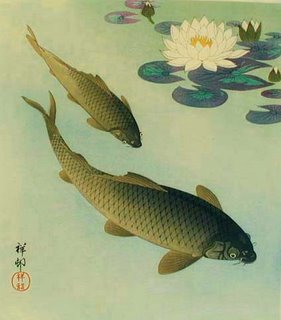

Ohara Koson (Shoson). 1877-1945 two carp and white lotus 1933 Recent studies at Harvard showed that people who’d spent hours playing a virtual-reality skiing game often dreamed later about aspects of the experience with a strong emotional prick — places along the course where they’d crashed, for instance — and generally performed better on the actual game after dreaming about it. It’s not exactly news to most of us that hot emotions and vexing problems tend to dominate dreams.

Believe me, I didn’t need a Ph.D. to decode the work worry in my stressful smoothie episode. But what is surprising, and to some extent vindicating to Freud, is just how emotionally beneficial our woolly night hallucinations seem to be. (Though he might be disappointed to learn how few of our dreams are overtly sexual: University of Montreal researchers, surveying 3,500 dream reports, found that just 8 percent of dreams for both men and women involved sexual activity.)

Whole Living, November 2010

Text by Louisa Kamps

gentle chime alarm clocks help you remember your dreams

Now & Zen’s Alarm Clock Store

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

Posted in Chime Alarm Clocks, Dreams, sleep

Lunar Healing By Deborah Willoughby

Did you know? The most fruitful time to undertake cleansing and detoxification practices is around the time of the full moon. The moon tugs not only the waters in the ocean but also those in our bodies, making it easier for them to release toxins. This is also the most auspicious time to begin a spiritual practice, particularly mantra japa.

The yogis say gazing the full moon strengthens the eyesight and the heart. In at least two Indian tribal communities—the Bhil and the Santha—walking in dew-drenched grass on the morning of the full moon night is believed to infuse the heart with the elixir of life.

Deborah Willoughby is the founding editor of Yoga International.

Tibetan Bowl Gong Alarm Clock and Timer Now & Zen

1638 Pearl St.

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

Posted in Dreams

harobu Christy Porter spends her days hefting crates and picking cantaloupe to feed migrant farmworker families in Southern California’s Coachella Valley. It’s hard work, and it shows. The 48-year-old nonprofit director walks with a seesaw gait on arthritic and overtaxed knees. Her arms are dotted with spider bites, her legs often splashed with oil from do-it-yourself attempts to fix the forklift.

Yet despite the dings, Porter seems to glide on a cushion of air. Like one of those airboats skimming over crocodile-infested waters in the Everglades, she rides a little higher than those around her. Her cushion? Not a daily meditation practice or a stress-busting supplement, but poetry. In her mind’s eye, its images and rhythms transform her everyday surroundings into something new and fresh.

Sure, it’s 120 degrees outside, but isn’t that brutal glare simply the world blazing, “like shining from shook foil,” as Gerard Manley Hopkins said?

And yes, she occasionally runs into sidewinders lurking under the warehouse stairs. But it’s hard to be spooked when she thinks of Emily Dickinson’s “narrow fellow in the grass.” “You know that starburst filter that photographers use to make everything sparkle?” Porter asks, shaking her blonde hair out of a big straw hat. “Poetry is like that to me.”

Indeed, healers through the ages have turned to poetry for its remarkable ability to soothe and console, much like prayer and song. The Iroquois fought off depression after the loss of a loved one by chanting a condolence incantation. In ancient Egypt, healing verses were written on papyrus which was then dissolved into a brew to be sipped.

Today, poetry is actually making its way into some doctors’ offices. Harvard poet-physician Rafael Campo, author of The Healing Art: A Doctor’s Black Bag of Poetry, is convinced that reading, writing, or reciting poetry can be therapeutic. In his own internal medicine practice, he likes to slip sheets of poetry among the prescriptions and brochures he hands out to patients.

Campo believes poetry can let people see illness differently (the starburst lens theory), as well as help them stay on an even keel amid life’s spider bites and forklift breakdowns.

While he’s certain that poetry is good for people, he can’t tell you quite why. “We’re just at the early stages of understanding the possible mechanisms of action,” Campo says. “But poetry probably affects people beginning on the level of the neurons in the brain stem. When patients read or recite poetry, the rhythms have been shown to improve the regularity of their heart and breathing rates.” Indeed, a study published in the International Journal of Cardiology showed that when volunteers read poetry aloud for 30 minutes, their pulse rates were slower than those of people in a control group who engaged in conversation.

Getting Acquainted with Poetry

For most of us, poems are something we left behind in high school or college. Here are a few simple ways to bring them back into your life.

• Go back to the beginning Try to remember something, anything, you liked that was read to you as a child: Mother Goose, Shel Silverstein, hymns or lullabies. The rhythms that moved you as a child can reach you now, and serve as your entrée to more adult fare.

• Read with your ears Poetry reaches us through our ears even more than our eyes. To experience this aural impact, go to a poetry reading or listen to tapes or CDs of poets reading their work. Or, as Denise Levertov once suggested, go into the bathroom and read poems out loud to yourself.

• Find your match “There’s a poem for everybody just like there’s music for everybody,” Christy Porter says. Don’t give up because you hate Hopkins or loathe Levertov. If intricate language is not your thing, try a plain-speaking poet like Mary Oliver or Billy Collins, the former U.S. poet laureate.

• Learn one by heart There’s nothing as handy as a great poem that’s filed in your brain, always accessible. Use relaxed moments when you’re walking or hiking to memorize a poem or lines from a poem. Poems learned by heart are “secret talismans,” Rafael Campo says. They can “ward off panic attacks while you’re flying on a plane—or be recited aloud while you’re doing yoga in the living room.”

• Write your own You don’t have to write poetry to benefit from the art form, but if you’re moved to try your hand at it, Campo recommends these guides: John Fox’s Poetic Medicine: The Healing Art of Poem-Making (J.P. Tarcher, 1997) and Louise DeSalvo’s Writing as a Way of Healing (Beacon Press, 2000).

adapted from Natural Solutions, by Anna Japenga, January 2004

Zen Alarm Clock for a Gentle Awakening Now & Zen

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

Posted in Chime Alarm Clocks, Dreams

|

|

|

|