Harunobu Suzuki, Beauty at the Veranda - Choose a gentle chime meditation timer by Now & Zen

You’re aiming for stimulated and focused—but not frazzled

Raleigh, N.C., businessman Buddy Howard used to feel his heart race and dread set in every time he thought about driving up profits at his equity research firm or was faced with an unwieldy project that seemed impossible to complete. Then his 11-year-old daughter developed anorexia—and he suddenly learned the difference between stress and stress. “Nothing comes close to the stress you feel as a parent when you’re afraid that your child is going to die,” says the 50-year-old father of two, who, seven years later, gets energized by the same deadline crunches that used to paralyze him. He now breaks large projects into discrete tasks that provide daily victories—the same bite-by-bite, pound-by-pound process his daughter used to overcome her eating disorder. And he’s altered his perspective on bigger earnings, focusing on the rush of the challenge and blotting out the fear of failure.

Stress has certainly earned its bad reputation, given the wreckage it causes: headaches, stomach pain, high blood pressure, insomnia, and mind freeze reminiscent of a crashing laptop. But it also has an unheralded upside. In normal doses, adrenaline and other “fight or flight” hormones improve performance and seem to even protect health. They increase alertness and motivate you to get things done by quickening your heartbeat, improving blood flow to the brain, and enhancing vision and hearing. And in small amounts, studies suggest, they boost the immune system and may protect against age-related memory loss by keeping brain cells active. University of Texas researchers recently found that those engaged in challenging and creative work enjoy better health—an advantage equivalent to being nearly seven years younger. “Your goal shouldn’t be to get rid of stress,” contends Esther Sternberg, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health and author of The Balance Within: The Science Connecting Health and Emotions. Rather, she says, you should aim for “the appropriate stress response.”

Extremely agitated. Getting the calibration just right can be tough, but it’s achievable: As Howard discovered, it’s often a matter of changing one’s perception of a challenge. Plenty of Americans have yet to figure out how. According to a recent survey by the American Psychological Association, nearly half say their level of stress has increased over the past five years, and fully one third routinely experience extreme agitation.

The problem with overwhelming stress? In the short term, the rush of stress hormones can make people less productive, even mentally paralyzed. Think writer’s block. When the overload becomes chronic, heart disease, depression, and an impaired immune system can result. An estimated 50 to 80 percent of people who develop depression have faced a major stressful life event, like a divorce or job firing, during the preceding three to six months and most likely have produced an excessive amount of the stress hormone cortisol. An October study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that heart patients battling chronic job strain were twice as likely as their more relaxed peers to have another heart attack. And researchers have been aware for some time that overanxious folks exposed to cold viruses are more apt to end up sick than those who aren’t.

“We think the system stops working appropriately when it’s constantly turned on,” says Sheldon Cohen, a professor of psychology at Carnegie Mellon University who first discovered the link between colds and stress. Chronically elevated cortisol levels lead to more colds and infections; depleted levels can cause an overactive immune system—and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

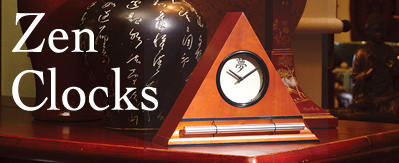

It's exquisite sounds summon your consciousness out of your meditative state with a series of subtle gongs.

The ultimate goal is to hit a stress response appropriate for a given situation: You want to be in low gear when you’re, say, watching TV, medium when you’re doing car pool, and high—but not overdrive—when you’re under a deadline crunch. High gear is what Sternberg calls the peak of the “stress response rainbow,” or the point where you’re at your most productive, able to focus on the task at hand with minimal distractions. Most likely, you’re sent into this zone by an optimal level of adrenaline, cortisol, and other hormones that increase your pulse, reduce peripheral vision, and improve blood flow to the brain.

Biology undoubtedly plays a role in how easily you hit the target: A study published last year in the journal Cell found that mice that adapted poorly after being put in a cage with bigger, more aggressive mice produced larger amounts of stress-related brain chemicals than those that adapted well. But modifiable beliefs and expectations factor in, too. Expecting that your life will be unchanging, for example, is bound to make you react badly to dropping house values and a child’s academic reversals, says psychologist Robert Rosen, author of Just Enough Anxiety, a new book that explains how anxiety can be a key to success in the workplace. “Buddhists have this idea that every time we breathe, the world changes,” Rosen says. A philosophy of acceptance allows them to make peace with what they can’t control—like an earthquake, inflation, or an oppressive political regime.

Once you experience the Zen Timepiece's progressive tones, you'll never want to meditate any other way. It serves as the perfect meditation timer.

Playing tricks. Sometimes, Sternberg says, the trick “is to fool your brain into thinking that you have some degree of control.” Researchers have shown that people produce more healthful levels of stress hormones when they’re told they have control over a stressor, whether or not they actually act—they have the ability to press a button to stop a loud, irritating noise, say, even if they don’t stop the noise. It’s all about being proactive rather than placing blame—as much as we’d like to put it on our parents—or sitting back and feeling helpless.

You might find a way, for example, to limit your exposure to a stressor. Duke University stress researcher Redford Williams says he reduced his tension over having to deal with endless E-mail messages by simply deciding to stop constantly checking his PDA after hours. (Bonus: Ignoring the pesky E-mail eased a bit of stress in his marriage, too, he says, since he could tell from his wife’s body language that “it wasn’t good for our relationship.”)

Or you might take a break to exert your mastery in other areas. Daniel Lobring, a 29-year-old public relations manager from Chicago, restores his “I can deal” feelings by picking up his drumsticks. He finds that drumming helps relieve stress headaches triggered by the pressures of organizing high-profile events for athletes and clients like ESPN. “I can only send out so many press releases and photos,” he says, “and it’s stressful, waiting and hoping that whatever I did will get some media coverage.” With music, he explains, he knows his performance rests completely in his hands. Even in times of crushing catastrophes, people can find relief by doing something purposeful: donating blood or cash after 9/11 or the Chinese earthquake; buying energy-efficient light bulbs or a hybrid car to ease distress over global warming and rising gas prices.

Unless you’re a natural-born optimist, of course, you may really have to work at seeing possibilities when times are tough. “The way to become more resilient is to live in the world, challenging yourself socially, psychologically, and intellectually,” contends stress and resilience researcher Mary Steinhardt, a therapist and professor of health education at the University of Texas-Austin. In a study published in the January Journal of American College Health, she found that stressed-out college students who were given four weekly therapy sessions—focusing on coping strategies, self-esteem building, and making interpersonal connections—increased their “stress resilience,” a measure of how quickly they bounce back after feeling stressed, far more than peers who didn’t get the counseling.

Steinhardt suggests pausing when stress hits to simply recognize its source, whether it’s an unrealistic deadline, a family reunion, or an inflating mortgage. Focusing your attention on the problem is key to identifying what you can control and accepting what you can’t and topreventing a panicked reaction from developing unchecked. If you’re not in a panic, you can offer yourself some coaching: Is anger going to be productive? Are you really (choose one): a bad employee, the black sheep of the family, someone completely incapable of handling personal finances?

Once you experience the Zen Timepiece's progressive tones, you'll never want to meditate any other way. It serves as the perfect meditation timer.

Be Happy Without Being Perfect, argues that we need to retrain our brains to think realistically. She recommends keeping a journal detailing any perfectionist tendencies, what’s gained from them (a spotless house, perhaps), and what’s lost (the novel waiting on your nightstand).

The guilt has to go along with the outsize expectations. Feeling overwhelmed by the needs of her husband and two kids and the demands of her employee relations job at computer maker Dell, Tonja Eaton of Round Rock, Texas, says she learned to put her wants (free time on Sundays, family evenings at home, belly-dancing classes) over her shoulds (visits with relatives, birthday parties for her children’s acquaintances, serving on a charity board) after joining a monthly “personal renewal group” focusing on work-life balance issues. More than 150 of these groups, based on The Mother’s Guide to Self-Renewal by Renée Trudeau, have formed around the country. “I’ve discovered a lot of creative ways to say no,” says Eaton, 36. “I’ve learned to make it a rule that a minimum of 50 percent of weekends be spent at home. We’re much more connected as a family when we do that.”

Understressed. While the health hazards of too much stress have been well established, too little isn’t good for you either, according to Monika Fleshner, an associate professor of integrative physiology at the University of Colorado-Boulder who has conducted numerous studies on the stress response. It could be that if the stress system isn’t activated often enough, she theorizes, it produces higher levels of stress hormones when it does get turned on. Like a muscle, it may need to be used regularly in order to stay in peak working condition. This could explain why some people fall apart when hit by a serious crisis while others rise to the occasion. If your body isn’t used to having challenges, Fleshner speculates, “perhaps when the stress response finally does get turned on, it’s hard to turn off.”

More established are the daily psychological consequences that stem from a lack of challenge: boredom, low energy, and a reduced sense of accomplishment. Teresa Walden, 44, grew all too familiar with these feelings in the years after quitting her in-house-attorney position in Austin to raise her two sons. She assumed that going back to her position once her sons started school would restore her mojo, but instead she felt stymied by the same old work. Ultimately, Walden decided to become a life coach. “I definitely feel more energized, more alive with purpose and intention,” she says. “It makes me a better mom.”

Whether you’re bored or overwhelmed, reaching the optimal stress zone requires bridging the gap “between your current reality and your desired future,” says psychologist Rosen. “There’s the voice inside you that says take a leap, go forward, but there’s also the voice that holds you back, warning that it’s too risky.” His five-step plan for getting through the gap: Identify what you want to change; imagine your desired outcome; assess your current situation; analyze what it will take to get you to your future goal; and take action to get there, setting one small goal at a time.

Yoga Stretch

Try the cure-all. Beyond using your mental processes to manage your response to stress, there’s that terrific physiological tool: exercise. Regular physical activity is the single best thing you can do to gain energy if you’re understressed and to relax if you’re frazzled, say experts. A 2007 study published in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine found that people who exercise at least two or three times a week have smaller increases in blood pressure, heart rate, and inflammatory chemicals when given stressful word-naming tasks than those who never exercise.

Researchers now think that exercise triggers the release of “feel good” endorphins in the brain, one of which, enkephalin, is believed to prevent the release of excessively high levels of adrenaline and cortisol. A session of exercise also triggers the stress response—a plus for those who are underchallenged. If you’re having either a stressful or a low-energy day, head for the gym or squeeze in a 20-minute ultrabrisk walk, recommends Mark Hamer, an exercise physiologist at University College in London. You’ll get the biggest benefits within an hour after you work out.

Any treat that activates your brain’s pleasure centers—a massage, a piece of rich chocolate, a funny movie—can similarly dampen your stress levels. Novelty is what you’re shooting for if your stress levels are too low: Head to an amusement park, sign up for a challenging art class, or take a rafting trip down some rapids. With practice, you can get good at avoiding that “most useless place…for people just waiting…for a better break…another chance,” in the words of Dr. Seuss in Oh, the Places You‘ll Go! His advice: “When things start to happen, don’t worry. Don’t stew. Just go right along. You’ll start happening too.”

By DEBORAH KOTZ for US News

Although meditation can be done in almost any context, practitioners usually employ a quiet, tranquil space, a meditation cushion or bench, and some kind of timing device to time the meditation session. Ideally, the more these accoutrements can be integrated the better. Thus, it is conducive to a satisfying meditation practice to have a timer or clock that is tranquil and beautiful. Using a kitchen timer or beeper watch is less than ideal.

Once you experience the Zen Timepiece's progressive tones, you'll never want to meditate any other way. It serves as the perfect meditation timer.

And it was with these considerations in mind that we designed our digital Zen Alarm Clock and practice timer. This unique “Zen Clock” features a long-resonating acoustic chime that brings the meditation session to a gradual close, preserving the environment of stillness while also acting as an effective time signal. The Digital Zen Clock can be programmed to chime at the end of the meditation session or periodically throughout the session as a kind of sonic yantra. The beauty and functionality of the Zen Clock/Timer makes it a meditation tool that can actually help you “make time” for meditation in your life.

It serves as the perfect meditation timer.

Posted in mindfulness practice