It's exquisite sounds summon your consciousness out of your meditative state with a series of subtle gongs.

Quieting the mind doesn’t have to mean shushing your many inner voices. By letting them have their say, you can discover the all-encompassing stillness of Big Mind.

In the 13th century, the great Zen master Eihei Dogen wrote, “To study the Self is to forget the Self.” Meditation practice allows us, through the simple act of awareness, to disengage our long-standing belief in a fixed identity. When we follow our breath, for example, through inhalation and exhalation, we are simply breathing, nothing more. Our thoughts no longer rule the roost. They cease to be the foundation of our identity, and our awareness expands. In this way, we begin to forget the self—that false construct of thoughts we’ve taken for reality for so long—and start to identify with a larger universal awareness.

As we progress in our practice, we naturally have strong insights. We might get a juicy taste of clarity; we might see all of our fears disintegrate. Unfortunately, when we get a taste of this “freedom,” we often develop a new set of ideas about what our meditation should be. Enlightenment becomes something outside of ourselves that we need to attain. We try to leapfrog over all that’s messy in our lives—the anger and jealousy, the hatred and fear, the weakness and petty acts. But we end up missing what meditation and enlightenment are truly all about.

There’s no way around it: The way to liberation points inward through the personally mundane, profane, and sacred. All of those voices in our head—no matter how scary, boring, distasteful, lascivious, or holy—must be recognized and accepted. If we deny or repress them, they only become more distracting, and our meditation practice suffers. This does not mean that we have to let them run amok; we can develop the capacity to contain a multitude of opposing voices without buying into any of them.

We can learn to recognize and accept these voices—and get a taste of emptiness—through the simple practice of Big Mind, a technique developed by Dennis Genpo Merzel Roshi, abbot of the Kanzeon Zen Center in Salt Lake City. The Big Mind process works within a familiar Western psychological framework, using the therapeutic tool of Voice Dialogue (created by Hal and Sidra Stone in the 1970s) while simultaneously pushing us through the door of Buddhist insight and wisdom. Big Mind uses a series of questions and answers that enable us to access and explore our different “personalities” and eventually transcend them.

Calling All Voices

Integrating Big Mind into your meditation practice (whatever its form) or daily life is quite easy. If you already have a regular meditation routine, do a minute or two of it to get grounded and comfortable, and maintain your usual posture. If you’re new to meditation, find a comfortable upright position (sitting in a chair is sufficient), take a few deep breaths, and relax as much as you can. Set aside 25 minutes for the entire practice.

The process of Big Mind entails consciously giving voice to different aspects of yourself. When you first hear a voice—you’re acting as your own facilitator in this process, but it can also be done with another person—ask that voice, preferably out loud, who it is and what its job is. The first one to connect with is your Controller. From your relaxed meditation position, ask yourself to speak with your Controller. Of course, you’ll probably feel a bit strange speaking to yourself this way, but you’re simply giving voice to the running dialogue that already exists inside your head.

The Controller is essentially your ego. Its job, as its name implies, is to control—your actions, your attitude, and whatever else it can wrestle into submission. You’ve likely met and probably struggle with this aspect of yourself. Ask the Controller about its job, then probe further and ask what it controls. My Controller controls everything—or, at least, wants to control everything: my actions, my thoughts, other people. It certainly tries to control all of my other voices. But this is neither good nor bad; the Controller is just doing its job. A key component of the Big Mind process is gaining the Controller’s—the ego’s—cooperation and not threatening it with annihilation, as spiritual training often does.

Just acknowledging that a voice exists and letting it have its say helps you develop a more open and trusting connection with it. Once you gain the Controller’s trust, you can ask it for permission to speak with your other voices; the ego is usually glad to temporarily step aside if it has been consulted. Next up is the Skeptic. Before asking the Controller to speak with the Skeptic, however, take a deep breath; when you shift into another voice, it’s good to give the mental movement a physical correlation.

The Skeptic’s job, of course, is to be skeptical. Of what? Essentially, everything: this Big Mind process, things you read in magazines, meditation, enlightenment… you name it. Let the Skeptic be what it is. It’s OK that a part of you is skeptical; it’s actually a good thing. If you didn’t have a skeptical voice, you might find yourself continually being hoodwinked. Ask the Skeptic what it has doubts about.

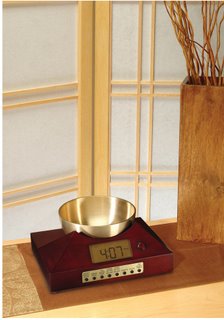

Once you experience the Zen Timepiece's progressive tones, you'll never want to meditate any other way. It serves as the perfect meditation timer.

Now take a breath and ask to speak with Seeking Mind. Shift over to this new voice. What’s Seeking Mind’s job? My Seeking Mind is constantly searching for something better: enlightenment, peace of mind, a healthy body. (Sometimes it seeks sweets, greasy food, and alcohol.) It will never stop seeking. Meditators often have a problem with Seeking Mind; they want to get rid of it, because it creates so much desire. But Seeking Mind is doing what it’s meant to do. It’s helpful to remember that without it, you might not be meditating in the first place.

Take another breath and shift to Nonseeking Mind. What’s its job? Explore Nonseeking Mind; ask it if it ever seeks. Nonseeking Mind is the state of meditation. There is nowhere to go, nothing to do. Again, this is neither good nor bad; Nonseeking Mind simply doesn’t seek. Take a moment here to notice how easy or hard it is to shift from one voice to another. Moving among your different selves helps you realize the empty nature of the self—that is, you have no static identity; you are continually changing. You might think your identity is set in stone (I am shy, I am angry, I am spiritual), but these are just voices floating in space; they’re not you. You’re much bigger than you think.

Now take a breath and shift into Big Mind. This is the voice that contains all the other voices. It is known by various names: the ground of being, Buddha Mind, Universal Mind, God. By its very nature, it has no beginning and no end. There is nothing outside of Big Mind, but Big Mind is a voice inside of you. Big Mind’s job, you could say, is just to be. Ask it what it does and doesn’t contain. Does it contain your birth? Your parents’ birth? Your death? Can you find its beginning or end? Does it contain your other voices? How does it see your daily problems? Stay in Big Mind for as long as you can. In this state, you have surrendered your personal ego (with its permission) to your true and universal nature. Becoming a Buddha is as easy as that, although letting go of your ego is often difficult.

Next, find your voice of Big Heart. Explore what it does for you and others. Its job is to be compassionate. How does it respond when someone or something is hurting? Does it take the form of tough love or tender nurturing or both? Does it have any limits when faced with suffering? Sit with this voice for a while.

Now shift back into Nonseeking Mind and stay with it for a couple minutes to end the meditation. Though you might want to stay in Big Mind forever, the simple fact is that no single voice is the stopping place; there is no stopping place. Continually working with and accepting all of your voices will, in turn, help you accept the myriad voices of others.

The Buddha at Home

The above exercise is a short example of working with internal voices and accessing Big Mind. There are, of course, an infinite variety of selves within you; working through the Controller, you can explore the ones you find personally resonant. Which voices you acknowledge depends on your life circumstances; perhaps you contain the voice of Damaged Self, Angry Self, or the Holy Father. Experiencing Big Mind is like taking an X ray of your true nature, your Buddha-nature, and projecting it onto a screen. The process gives you the clarity to recognize various aspects of yourself and the ability to move easily among your many voices without getting bogged down in or attached to any one voice (even Big Mind). When, with practice, you develop that mobility, you become free to respond with ease to anything that arises. This is meditation in action.

Once learned, the Big Mind process can be used at any time during meditation practice or throughout the day. If you’re feeling particularly angry during meditation, you can connect with Angry Self, let it have its say, and move into Nonseeking Mind or Big Mind. Play with your various voices and see what you can find.

Many of us spend countless hours in meditation trying to fix ourselves so we can attain spiritual knowledge. But the truth is, there is nothing to fix. We—all of us—are already Buddhas. There is nothing to add, nothing to subtract, and nowhere to go. By working with the very intimate voices of our own minds, the Big Mind process lets us “stay at home” while simultaneously acknowledging that our “home” includes a lot more than we think. After all, “To study the Self is to forget the Self.” Studying the voices in our heads is a good way to start.

Although meditation can be done in almost any context, practitioners usually employ a quiet, tranquil space, a meditation cushion or bench, and some kind of timing device to time the meditation session. Ideally, the more these accoutrements can be integrated the better. Thus, it is conducive to a satisfying meditation practice to have a timer or clock that is tranquil and beautiful. Using a kitchen timer or beeper watch is less than ideal. And it was with these considerations in mind that we designed our Zen Alarm Clock and practice timer. This unique “Zen Clock” features a long-resonating acoustic chime that brings the meditation session to a gradual close, preserving the environment of stillness while also acting as an effective time signal.

adapted from Yogajournal.com by John Kain has written for Tricycle, Shambhala Sun, and the Web site Beliefnet. A meditator since the early 1980s, he lives near Woodstock, New York. For more on Big Mind meditation, visit www.zencenterutah.org/bigmind.html.

It's exquisite sounds summon your consciousness out of your meditative state with a series of subtle gongs.

Now & Zen – The Gong Meditation Timer Store

1638 Pearl Street

Boulder, CO 80302

(800) 779-6383

orders@now-zen.com

Posted in Meditation Timers, Meditation Tools, mindfulness practice